|

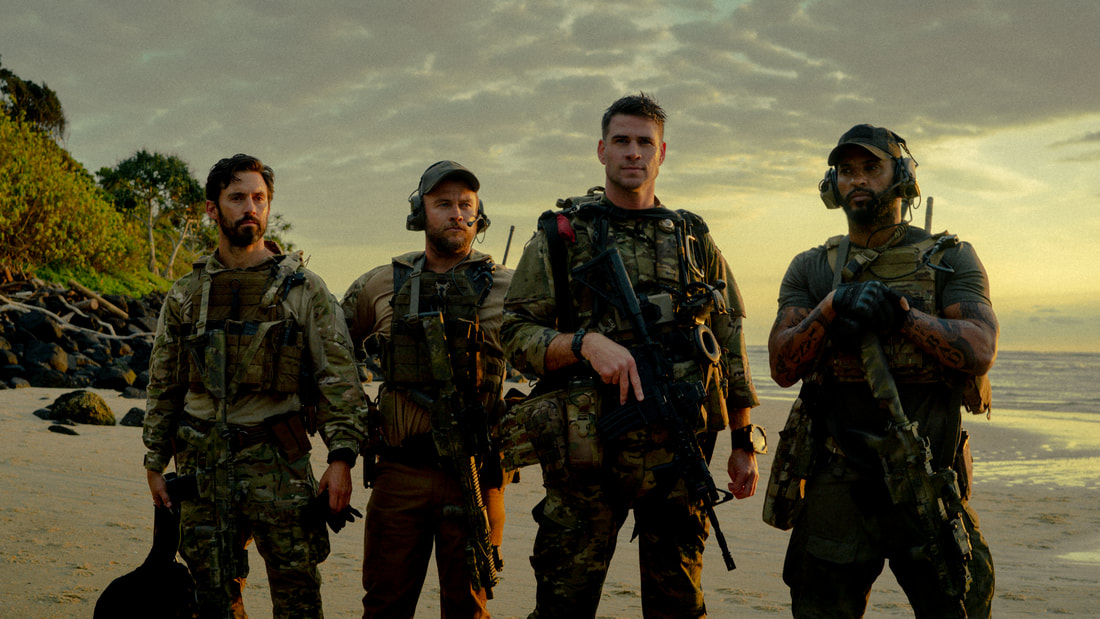

Review by Daniel Lima Only a few years after the end of America’s longest war — the last large-scale engagement of the Global War on Terror — and amid the federal government’s culpability in Israeli war crimes, it certainly does not feel like the public is yearning for a story about the righteousness of the U.S. military. Indeed, in the past two decades, it appeared that the classic rousing war picture has fallen entirely out of fashion, even at the height of pro-war sentiments in the aftermath of 9/11. How, then, do you make a 21st-century war movie? The latest attempt, Land of Bad, is more interesting in how it navigates that question than in the form it ultimately takes. Liam Hemsworth plays a young U.S. Air Force officer attached to a squad of special operations soldiers on a covert mission to extract an American asset from a militant compound located in Southeast Asia. When the mission goes sideways, he finds himself alone in hostile territory. His only companion is the voice of a USAF drone operator, located thousands of miles away, who attempts to guide him to safety. Perhaps the most important detail that separates the 21st-century war film from those of decades past is the kinds of soldiers and conflicts that tend to be the focus. Gone are the grandiose, large-scale battle scenes with thousands of combatants; America has not been in a war against a uniformed adversary that could match its military might in nearly a century. Instead, the war film has evolved into both a more character- and process-focused genre, delving into the personal lives of service members and the meticulous detail of their combat missions. Often, these are stories of elite special forces carrying out specialized missions rather than regular troops. Land of Bad follows this trend to a T. There are only a handful of named characters, all called upon to do a specific task. A good amount of attention to detail goes into getting all the military jargon correct, all the different roles the men in the squad would take, the numerous agencies that would come together for a mission like this, the approach these men would take in completing it, and of course, their emotional state and commitment to duty. Most obviously, this results in a lean, straightforward narrative that allows for more emotional investment in these characters as people rather than representatives of an ideology of American superiority. As the men banter, we see them not merely as men in uniform but as people performing an incredibly difficult job. As they go about it, there are stakes beyond whether the government completes a task successfully. To that end, this film is a mixed success. Hemsworth gives a surprisingly natural performance, but considering his character is largely reactive to an evolving situation, not much time is spent developing him. As the drone pilot supporting him, Russell Crowe has a much meatier role and makes the most of it. As an anti-authority figure who nevertheless is a stickler for adhering to a particular order of doing things and feels great responsibility towards the operators, he finds himself partnered with. Even though he spends most of the movie in front of a computer screen, I found myself wishing more time was spent with him than the guys with guns in the jungle. The condensed perspective of this narrative, and the many others like it, does fulfill an ideological purpose. While focusing on these small teams is more reflective of U.S. military operations today, it also allows filmmakers to sidestep the many concerns surrounding American military activity abroad. Detailing the immediate hardship of a soldier under heavy fire with no way to retreat means the script never has to justify why that soldier had to be there in the first place. Naturally, such is the case here. While the opening text crawl mentions that the Susu Sea is a hotbed for extremist groups, where exactly this compound is located is never specified. Going further, the film never clearly defines the actual adversary the Delta Force squad is there to combat. One antagonist is named, but what his goals are, what his activities include, his brand of politics, and his gripes with the United States are not elaborated on. The man is fully willing to kill children, which, of course, makes him a bad guy. Then again, as anyone who has been paying attention to the news in the past four months is aware, the American government is hardly one to throw stones.

This ambiguity is undeniably an effort to obfuscate the underlying assumption of all the war movies: the U.S. military agenda worldwide is inherently good, all those who support it are heroes, and all those who oppose it are villains. Of course, bad politics don’t make a bad movie, and there is no shortage of action movies doubling as propaganda that are quite enjoyable. However, with such an establishment-friendly and conventional worldview and a general lack of character development, a film like Land of Bad must deliver truly remarkable action and thrills to rise above a sea of similar works. That, more than anything, is its greatest failure. The set pieces here are decent enough by the standards of a mid-budget American production, thankfully keeping the camera steady throughout its handful of shootouts and melees and featuring some actual practical explosions. None of it, however, is particularly memorable, lacking a sense of geography or choreography that properly utilizes the environment. Without anything to make it distinct, the action fades quickly from memory. With it goes anything notable about Land of Bad, barring one fun performance from Russell Crowe. As run-of-the-mill as any other modern attempt at a muted, chest-thumping love letter to American imperialism, one can’t help but wish that this film took a more overtly jingoistic approach to the material if only to have something actually interesting to dissect. Sadly, the only purpose this serves is to illuminate how much times have changed. Land of Bad arrives in theaters February 16. Rating: 2.5/5

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2024

Authors

All

|

|

|

disappointment media

Dedicated to unique and diverse perspectives on cinema! |