|

Review by Sarah Williams

Actress Kate Lyn Sheil exists in a sort of Brooklyn apartment movie stardom, a household name among mumblecore fans yet virtually unheard of to anyone else. These low-key indies have a sort of cult following, raging from the self-insert talky sex comedy (Joe Swanberg’s Autoerotic and The Zone) to the sensorily overloading, creative art horror of Adam Wingard and Amy Seimetz. Materna rests somewhere in the middle. David Gutnik’s directorial debut, produced by two of its four lead actresses (Jade Eshete and Assol Abdullina) follows in the tradition of films like Short Cuts and Magnolia to blend a pseudo-feminist subway story of four women who meet by chance. The film is divided into four sections, each centering a different woman, and particularly their relationship as either a mother or a daughter.

The weight of these stories varies wildly, everything from passivity to a child’s bigotry, reproductive pressure, and found family, but each of these feels like its own movie. There is something to say for the treatise Materna makes on private lives, on the rich complexities of passing strangers, but the omnibus of short films we are essentially given seems to merely skate the surface. Its attempt to give a unifying scope of womanhood through its packaging is especially strange, given that there is little universality outside a vague idea that they are all connected to the idea of motherhood and maternity.

In terms of the individual segments, they are all wildly uneven. From a vision and performance perspective, Sheil’s is the strongest, a near horror psychodrama on the pressures of fertility. Though a bit shy on the script, the segment holds a deep weight of pressure between Sheil’s Jean, a VR tech, and her mother who wishes her to start a family or at least freeze her eggs. This pressurized fountain of youth is further confounded by Jean’s unplanned pregnancy, and the suffocation of the situation is clear. Better written, and by the actresses they center, are two others. One, where a woman detaches from her Jehovah’s Witness mother, and finds surrogate family in an older colleague, is strangely touching, while the final segment is quieting, about three generations of Kyrgyz women and the ghosts in their lives. This segment is what Materna should be pushing towards, a clear, cyclical connection to the maternal lineages it teases.

Most baffling is one chapter starring Lindsay Burdge (fans curious about a new collaboration with Kate Lyn Sheil may be disappointed that this is far-flung from the short buddy comedy Super Sleuths). Her conservative mother deals with her son’s suspension from school, and the segment falls into pained New York liberalism as her family gathers to interrogate his racism. It’s the most chronologically rooted segment, Burdge’s out of touch mother taking away the kid’s Fortnite access, and it messily tries to bite at group-think and cancel culture while plodding into message movie territory without having the grounding to do so. Because of its constant grab for social relevance, Materna bites off so much it never quite gets deep into its false-intersectional tote bag liberal feminism to handle the weighty omnibus of motherhood it wants to be. Materna is now available on VOD. Rating: 2.5/5

0 Comments

Review by Sarah Williams

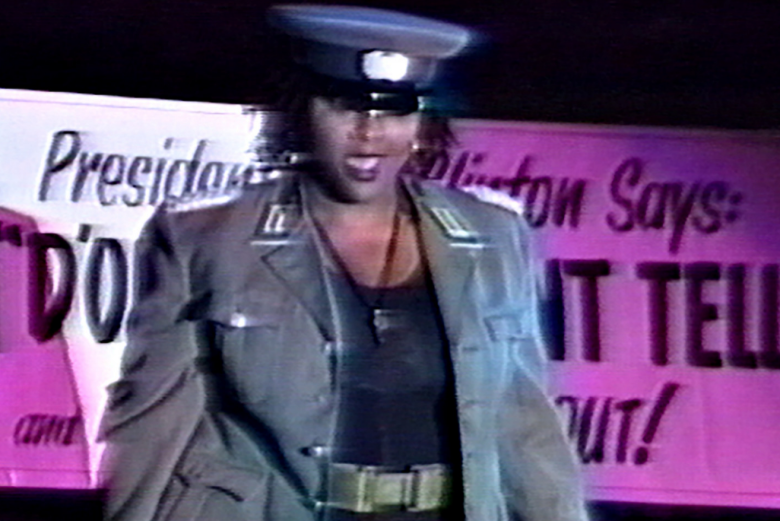

Sex positivity is all too often centered back to male pleasure. With frank discussions on intimacy and kink often centered on heterosexual structures, films like Kamikaze Hearts, Bloodsisters, and the films of experimental film pioneers document a queer liberated desire, specifically lesbian community, long before Hollywood acknowledged us. Receiving a rerelease from Kino Lorber, Michelle Handelman's bitingly funny documentary about the San Francisco leatherdyke community comes best served at a time where eroticism has been made absent from mainstream cinema. Bloodsisters has a dykes to the front agenda, proclaiming itself to be an A-Z guide to leather, lesbians, and left radicals.

Sadomasochism here is less about personal fantasy, and more a power structure created to build its own society. Domination is used to build trust: BDSM becomes a learning experience for the subjects. They build their communication with each other, and learn to set boundaries. It's a language of physicality, a societal vulgarity that feels truly liberatory in the guide Handelman's camera constructs. In places, the subjects indicate that it's less the fist inside of them or the whip, less the sensation itself than the trust and adrenaline rush that brings them to it. The key to this power play is how different it feels from some heteronormative kink seen today. They are clear that death should never be a risk, that this is pleasurable BECAUSE of consent, and that the danger in this is acknowledged, and given a reminder to check in with your partner. The film is also incredibly quotable. "I'm butch but I primarily identify as a faggot, I'm very effeminate," one dyke says, "You're like a prep school butch," another responds. The refreshment here is the frankness of the language. Crass language, open sexual discussion, and terminology exclusive to this community is on full display, and the comfort the subjects have in this discussion is commendable. The deep dive allows so many voices to chime in their experiences, and there's a sense of camaraderie with the filmmaking team.

An important distinction made by a few of the documentary's participants is how they wish to be labelled as dykes, not lesbians, asking for an identifier ever further from being socially acceptable. This community is about subversion — it is about looking palatable respectability politics in the eye and saying if you don't want me for what I built to survive under you, you do not get me at all. The line "fist fuck the system" defines what these leather dykes believe. They believe in queer liberation without censorship, that it is better to find freedom in each other than respect in society. Of course, there are limits, in that this is a group that is mainly white lesbians.

Bloodsisters is a rarity because it calls out the dangers of kink without communication, and it makes it clear there are two halves to this equation. Even in all the playful fisting jokes, there are clear conversations about sexual power, and equality. Rarer still is how the film is a celebration of lesbian masculinity, dominant femmes and whiny butches, social roles and dykes refusing male pleasure. 77 minutes in the leatherdyke gives us more butches than the mainstream film industry has in twenty years. This is the kind of film we need to have a return to conversation. Not kink at pride discourse, not sex scenes in cinema discourse, but a clear, open discussion on healthy sex positivity free from a patriarchal structure. Bloodsisters is now available on VOD. Rating: 4.5/5 A dreamy, plotless year in the life, Stop-Zemlia creates an otherworldly parallel reality of the end of adolescence, blending suspended fantasy of the teenage existence created by idealisation, and the near-documentary realism of its naturalistic structure, The Ukranian film is light on exposition, instead choosing a fluid approach to structure, blending past, present, and future in a thoroughly modern coming of age. Where the film falls short is not its lack of structure, but its lack of focus, flitting between a lot of serious mental health topics to the point it feels odd these are left unspoken. Masha (Maria Fedorchenko) is feeling every emotion all at once. She and her best friends Yana (Yana Isienko) and Senia (Arsenii Markov) often have sleepovers all sharing her bed, a natural closeness they don’t realize is going to leave their lives when they grow. Her attraction to Sasha (Oleksandr Ivanov), and a mysterious admirer on Instagram she often confesses to are both hard for her to define, and she is well aware of how messy feelings can be when young. While somewhat fiction, Stop-Zemlia more closely resembles Sébastien Lifshitz’s documentary Adolescentes than the early comparisons to Euphoria it has received. The non-professional actors lead these characters to be played just like teenagers living their lives, so the film feels documentarian as they’re hardly fiction. Of course, anything with teenagers, bisexuality, and pastel-llit parties tends to receive the latter analogue nowadays. Where the film falls short is that director Kateryna Gornostai has fallen in love with her characters deeper than we ever could. Though two hours is a short time to encapsulate a year of life, even at a time when growing up feels so hurried, this feels like nothing was cut from every idea for a scene that was thrown around. While some scenes — like a class of teenagers throwing bags and classroom things at one another, an exercise in waning childhood they only pretend is ironic — create atmosphere, other elements are remnants of an attachment to sequences we do not need.

The suspension of reality works best here to simulate what it feels like to be young, and to see yourself as a wild creature. The lights of a party strobe, bodies meld into each other, but this comes with an awareness that there is artifice in this indigo-dazed perfection. There is an idea that this is only some teenage dream, that their love can be so idealized, bodies never shallow but spouting poetics about kissing to the beat of the changing colors. What is present is that awareness that Stop-Zemlia is so often that fantasy you build of your teenage years, hormonal egos rushing to create that feeling of the mundane being on top of the world. It's refreshing how natural it feels, however, that the tougher parts of growing up are spoken of as jarringly casually as they are among peers. The films relaxed, ambiguous approach to queerness among girl friends is particularly well done as well. At one point, one of Masha’s classmates says “I just like feeling things, it’s better than feeling nothing,” which just about defines the everything at once scattershot approach and energy that Stop-Zemlia has. Stop-Zemlia is screening at the Berlinale Summer Special which runs June 9-20. Rating: 3/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Seemingly positioned to be the annual male-gazey low-budget horror advertising lesbian leads that inevitably turns up on VOD every year, The Retreat surprises by taking tired slasher tropes and instead giving the power back to its leads. A fairly straightforward cabin in the woods meets The Most Dangerous Game romp is gory, yet has a bleeding, beating heart beneath the surface.

Sarah Allen and Tommie-Amber Pirie star as new couple Valerie and Renee, who spend a weekend at a Canadian bed & breakfast, enticed by a professed atmosphere of inclusion, and the friendly gay married hosts that are advertised, on a trip to help plan a wedding. What they find, however, is a trap many before them have fallen into, where hunters are out for blood, and they have to fight their way through the night. So much queer horror exists in character only, not commentating on any intersection between identity and the coming action, or worse, does so in a ham-fisted manner. The Retreat is an oddly clever take on the ‘rainbow-washing’ brands use to obtain a niche of customers, plastering on a facade of acceptance, pride, and solidarity just to corner another niche of the market without any radical action of tangible support. Here, it’s not just quarters spilled, but blood.

Hunters out for blood of the visitors, prominently a gay audience drawn in by promises of community, await them, and a You’re Next-style slasher progresses. It's formulaic at times, and sometimes falls into some predictable story beats, but solidly bloody. Though a clever social satire, there are some moments that feel like they’re poking fun at the class of some of the ‘white trash’ locals, but this isn’t exactly unusual in genre film. Allen and Pirie have an easy chemistry, and its lovely to watch their relationship strengthen through the night. Both play atypical final girls, smart and well-versed on the classic horror movie mistakes, and its nice to have heroines who act like they’ve seen Halloween and Scream at minimum.

What elevates The Retreat is the potential secondary metaphor, that it can be read as a satire of how queer horror fans are baited with promises of seeing ourselves onscreen, only to be mocked, fetishized, or have the characters placed there for us brutally slaughtered at the start. I’d worried this would be exactly like so many of these films, only to be pleasantly surprised that the gays get to win, and poke fun at this a bit in the end. The Retreat is now available on VOD. Rating: 3.5/5

Review by Sarah Williams

The long-take opening shot of Amundsen, The Greatest Expedition, a thrilling plane crash, is a high that's not quite returned to. The Roald Amundsen biopic by Norwegian Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man Tell No Tales and Kon-Tiki director Espen Sandberg is a road to an adventure that's never truly felt. Charting the lead-up to the explorer's renowned (and dangerous) polar exploration, the film falls flat when it eventually reaches the end of the world, with a danger that's never felt like that first aeroplane.

Leading the first expedition for the South Pole in 1911, and reaching both poles in 1926, Roald Amundsen (Pål Sverre Hagen) is given the Spielbergian-lite biopic treatment. Most of the film's strengths lie in galas and dinner meetings, scenes building anticipation for the expedition that feels far lower stakes than it should. Perhaps the focus isn't on the trip, but on the life leading to it, but with a team who is strongest with idolized heroes and glamorous set pieces, introspective, moody, character studies don't quote work. What does shine in these more mundane sections is the outside world around Amundsen. The period setting is beautifully assembled, and for a more minor release, one that's taken two calendar years from premiere to US release, it's startlingly detailed and accurate. The supporting performances are worth noting, with appearances from Christopher Rubeck and Katherine Waterston livening the affair.

What's baffling here is making a film where the selling point is the expedition, and then trying to study a character that's left dull instead. Amundsen's strained family relationships, and the romantic subplot, don't give any of the actual interesting aspects of his character, the lack of fear and why he would want to go where no man has before. The men on the expedition aren't particularly characters we care about, and it all feels far too low stakes. The film is part adventure saga, part slow period drama, and it doesn't quite stitch together. All we know in the end about Amundsen is that he is driven by ego, something that can be extrapolated watching countless other works about the renowned men of the time.

With set pieces like a Pirates of the Caribbean movie, and the storyline of a Thanksgiving day release, Amundsen is a film that would have replayed the best at a Sunday afternoon matinee, the kind of harmless but forgettable film you see with your parents, shrug, and learn a few history facts from. It's hard to hide that it feels like a relic from fifteen years back, dated and formulaic, destined to be played in a freshman year geography class's end of year explorers unit. It's hard to judge it as a bad film, because it's not all that poorly made, this just feels like deja vu of years past, and the few highlights and surprises are never quite allowed to shine. The issue isn't poor craft, or an offensive misstep, Amundsen just that brings so little to the table that doesn't call back a forty year old formula. Amundsen, The Greatest Expedition is now available on VOD. Rating: 2/5

Review by Sarah Williams

In The Affair, originally titled "The Glass Room" (a title change that's truly baffling given how much less unique the former sounds), Carice Van Houten is a gem in what is an otherwise messy and distant lesbian love story. Liesel (Hanna Alström) is content in her marriage to Viktor (Claes Bang), when her dynamic with close, free-spirited friend Hana (Van Houten) shifts. Liesel turns away as Hana confesses her love, turning away while things are still easy. Over the years, Hana tries her best to push away male interest as she waits for Liesel to be ready to love her back. What follows is a lengthy saga across Europe, of two women who may be the right person for each other, but don’t meet at the right time, and an eclectic combination of talented actors, some working on autopilot here, it’s surprising all speak the same language.

The architectural setting at the root of the story most easily draws comparisons to Reaching for the Moon, a Brazilian adaptation of poet Elizabeth Bishop's relationship with architect Lota de Macedo Soares, which painted a passionate, conflicted romance and utilized the house alongside their relationship. Though the modernist house in The Affair, by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, may be better known, the structure feels like merely a setting even though it's so tied to Liesel's past. They anticipate the significance, but the many, many scenes shot within never quite let the room breathe as the character it's supposed to be. The film has got an odd bend to how it pursues its leads' everlasting desire to be together no matter what, as it's incredibly pushy even when the chemistry dries. Instead of making the love between Liesel and Hana more present, there's an emphasis on leaving, and specifically a focus on their husbands in that regard. We see Czechoslovakia fall to the Nazis, and we see a push to leave behind this glass room, and the past significance it has to their families. The very Aryan Liesel pushes to leave firmly, and it's so in contest with her husband it makes an awkward message considering his firmly noted Judaism in an era of violent antisemitism.

Even though the chemistry lacks at times, the end result of their relationship is sweet, and feels like a worthy payoff to the very slow road there. Claes Bang is surprisingly the highlight out of the actors, charismatic enough that Viktor is more than just the omnipresent, foreboding husband character that is usually present. Visually, the whole deal is a lovely pastel watercolor, with soft lighting and colorful costuming in contest with some of the darker settings.

It's quite clear that this was a novel before it was a film, and perhaps a lot of these weaknesses lie in being an adaptation. Of course, there's not all faults, as it's got a genuine, happy ending that's more than deserved, which breaks a lot of tragedy porn trends within lesbian film. However, some of the flaws don't lie in the source material, with uneven pacing that drags heavily for two acts, and some choppy and distracting editing that takes away a more lucid flow detracting from the romance. It's a solidly middle lane romance, one with a happy ending and talented actresses working on autopilot, that will have a few cult followers, but mostly viewers giving it a decent shrug and moving on. The Affair is now available on VOD. Rating: 3/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Love letters are the most common surviving relic of relationships between women of the past. Diaries and notes are pieces together, getting a half idea if love affairs that, while not outwardly forbidden, went unnoticed in a male-driven society. These female friendships were often tinged with a burning passion, commitment beyond that to a husband. The World To Come is a chain of such love letters and diary entries, threaded into a delicate love tragedy, that though flawed, is so believably rendered, with a pleading, beating heart of chemistry.

Abigail (Katherine Waterston) has recently lost her daughter from diptheria in late 19th century Upstate New York. A winding diary entry monologue details her detachment from her husband and child, and how she feels that she has become her grief. Redhead whirlwind Tallie (Vanessa Kirby) falls into her life one day, met at the edge of their property, and the two women begin to meet often, and grow close, coming alive with the company. It's a romance film, but it's more about the awakening than anything. We see Abigail roll over in the night and express her newly articulated discomfort for physical intimacy with her husband before we ever see her and Tallie do the same. This, in large part, is a film about ecstasy, and finding something holy in love. Tallie's visits come weekly, and they're a light in Abigail's life that leaves her breathless and excited each time, even when it's something as simple as plucking chickens together. That religious ecstasy climaxes when Tallie's visit ends in a gently burning kiss. Abigail seats herself on a bench when she shuts the door behind her, and lays back against the table. Her arms outstretch, her neck cranes back, and dark hair and billowy dark sleeves and skirting pool around her. She looks to be sacrificed to some power above, spare for a sigh of pleasure that comes with having known joy in love that day.

For Abigail and Tallie, finding pleasure becomes like heaven. The two women find a certain freedom in their escapes together, laying in a small clearing in the forest for gentle affection. Small rays of sunlight find them here, and they are able to strip down a bit and blend in with nature in their joy. Abigail saves her money to buy an atlas, as she dreams of far off places, and longs for that tactile feeling of pages beneath her fingertips. For her, in those coming months, Tallie will become her world, and she'll be that atlas of pages of memories she can take to love on with her. Abigail once says "And you know what memory it is that I most cherish? It's of your turning to me, with that smile you gave me, once you realized that you were loved", and it really sums up the power she finds in having this brief love, and in being able to make someone else feel that same joy she does. Cliche, but it's the power of a good love story.

The film is far from without its issues, and they may overwhelm it for others. While many praised the score as innovative and beautiful, a fellow disappointment media critic referred to the sound as "like someone had deep-throated an oboe" after the Sundance screening. This is a minor and subjective issue, however, compared to the film's messy messaging when it comes to the finale. A turn for tragedy breaks the rhythm of the film, and feels unnecessarily cruel (not to mention the misplaced sex scene) when this plot point is there for a message that love can be what awakens you, and that the memory is important. There are so many less jarring ways to do this, that don't feel like a tonal pitfall, and changing the original short story ending feels warranted here. Abigail's diary entries sometimes feel like a copout to avoid showing the intricacies of dialogue, though they're usually wonderful. Also, this is a movie starring Casey Affleck. Do what you will with that. The World To Come has its missteps, but the fantastic chemistry of those first two acts make it emotionally devastating enough some of its issues can be forgiven. It's bluntly realistic enough about each of the two women's situations, whether they be grief or an unhealthy relationship. This frankness makes the moments we don't see easier to fill in, easier to see what level of passion Abigail and Tallie have between the scenes. With splendid craft all around, it's an ideal Valentine's Day alone and cry movie. The World to Come hits theaters February 12 and VOD on March 2. Rating: 4/5

Sofia Coppola seems to be leaning further and further into mass appeal. If using any adjective to describe On the Rocks, it would be “watchable”. No matter how inconsequential the film gets, it’s never truly boring, and its pre-treaded path makes it a fairly certain viewing experience with your parents over that fall break, something you’ll finish watching, say “Hm, that was perfectly fine”, and never watch again. The heist tale of Bill Murray's playboy father to Rashida Jones’s anxieties over her husband's whereabouts isn’t bad, but it never says anything interesting enough to warrant memory in any canon, hardly more of a drop in the ocean than A Very Murray Christmas.

Laura (Rashida Jones) begins to suspect her husband Dean (Marlon Wayans) may be having an affair. It's not that he seems unfaithful, but the jewelry store sightings, long work dinners, and time away toy with that little voice in the back of her head, and her idea of her father's (Bill Murray) infidelity, and his help investigating only lead her suspicions to rise. Father and daughter begin a series of late-night stakeouts, bathing in his wealth as they debate the nature of staying together and how this affects the whole family, and old bitterness at fatherhood comes to rise between glasses of champagne and fine art. Coppola is the closest women have gotten to that common conversation canon of getting into movies masters — men like David Fincher, Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Edgar Wright, and Christopher Nolan who have become household names among twenty-somethings that like to claim to be into movies when they’re just starting out. From time to time, Twitter threads crop up, asking readers to name a female director that isn’t Sofia Coppola or Greta Gerwig. Its not that she’s undeserving of this pedestal of popularity, but the steam seems to be running out, and it's worth noting the Coppola family is an easier entry to the film industry than most get, but there’s no denying the great cinema we’ve gotten from her in the past.

What is missing here of Sofia Coppola’s signature charm is her style. The Virgin Suicides and Marie Antionette are as great as they are because they let darkness exist within their hyperfemininity. On the Rocks may believe itself to be a maturation, but in doing so it loses the feminine trappings that have created that distinctive style. If anything, the style here is Apple TV. Sleek and overpriced, like an iPhone, there’s more concern for caviar in a convertible than relatability as a woman in this world. It’s streaming service fodder through and through, and though tightly written, I can’t imagine anyone scrambling to rewatch beyond the novelty of a new Coppola film (though it is less disappointing than Gia Coppola’s newest entry Mainstream, a shallow and buzzy social media caper).

If The Virgin Suicides is the wide-eyed ingenue, then On the Rocks is not a wise mother, but a tired secretary of a film. It feels like it’s running on autopilot, an algorithmically determined family drama until the end, where it becomes a lovely acknowledgement of Laura’s anxiety and self-worth, and the ideas our childhood leave us with about family. Jenny Slate is an absolute star here as well, popping up every thirty minutes or so at Laura’s kids’ school to vent her own frustrations on affairs from the side of “the other woman”. This isn’t just a film about the struggles of marriage, but a map of everyone hurt by the lack of communication in an affair. It is nice to see a Black family get their bland wealthy family drama, but there are some tropes that are stumbled into, even if unintentionally. It's common that Black families in popular media aren’t homogenous, and the mother is always mixed or lightskin when one parent is darker. It’s a trope that’s followed here, and whether or not it’s intentional, it’s a shame only lighter black women get these glossy romcoms about their families, and On the Rocks only makes it clear how deeply entrenched colorism is in Hollywood. Perhaps I am being unfair to On the Rocks due to its all-star pedigree. For bourgeoisie anxiety drama, it’s very well made, and Bill Murray and Rashida Jones make charming co-conspirators. However, it does everything it can to pull the relatability out of anxiety, staying in the New York high society of yesteryear, a world that feels so alien that even the real conflicts presented start to feel like trifling rich people problems. It’s a shame Sofia Coppola has matured away from her distinct style, as On the Rocks is the just fine-est film of the year. On the Rocks streams on Apple TV+ beginning October 23. Rating: 3/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Yet another “never before seen footage” type doc, Cured does its job fairly well. It is the story of how gay activists went toe-to-toe with the APA to get homosexuality removed from the DSM listing as a mental illness, and its yet another gap filled in LGBTQ history (and the ludicrous claim that the removal of the listing 'cured' every documented homosexual). Newspaper clippings, archival footage, and narration blend together to give a clear picture of this law, and its removal, an end result that doesn’t leave much more than the true story itself.

Gay history is often viewed as dominating relationships between aristocratic men and peasants in Ancient Greece and Rome, then Stonewall, the the United States Marriage Equality Act in 2015. It’s a Euro-centric view of LGBTQ history, skipping around to just the parts that are harder to erase. Even within the US, so many smaller legal victories towards acceptance are overshadowed, and it's great to see this important act of removing the dehumanization of love documented the same way this more commonly discussed history is. It’s hard to believe that the heads of the scientific nation would go out of their way to list homosexuality as a mental illness, but this is conveniently scrubbed from history, always discussed as pure phobia, and not societal classification that this is defective. Of course, unless outspoken, lesbians were instead ignored or written off as close friendships, an odd safety. These kind of simple, direct docs may start to blend together, but it is important to note that we now see gay and trans history documented and released the same way other stories of a fight for equality have been. While some of these types of films may come off as merely serviceable nonfiction storytelling in a slate of imaginative fiction at an LGBTQ centered film fest, like Outfest or Frameline, this fits a specific niche. It’s educational content that doesn’t need to be sought out, and is made for more mass appeal in terms of filmmaking sensibilities, as this is something that many will genuinely learn from.

Kay Lahusen joined other protesters on a picket line in front of Philadelphia’s Independence Hall on July 4, 1969. This protest marked the fifth “Annual Reminder,” a march held yearly on July 4 to remind Americans that LGBTQ citizens were denied basic civil rights. From Cured, directed by Patrick Sammon and Bennett Singer. Photo credit: Nancy Tucker, image courtesy of Lesbian Herstory Archives.

Even though Cured isn’t the most adventurous in terms of filmmaking, it fits into a key sector of cinematic purpose. It’s the sort of film that you’d find on PBS late at night, the way information seeps into your brain when the moon comes up, an after dinner haze where you don’t realize you’ve learned something until it slips out in conversation at a dinner party. It’s great to see this assembled in a manner that normalizes it as a piece of history, the same kind that plays on the TV wheeled into a classroom on a substitute teacher. It’s LGBTQ history 101, but our history is hardly told, and it’s nice to be able to watch something that unpacks it so clearly.

What I do want personally is for these historical documents to focus less on suffering and discrimination, and to see more gay and trans joy when history decided we did not exist. Even though it is shown through the eyes of the family around them, Netflix’s A Secret Love was a step in the right direction, showing the love between an older lesbian couple that had flown under the radar for so long. Of course, seeing the truth is never troubling, but it would be nice if the media a heterosexual audience sees shows more than just our oppression, and for them to see that light was even possible at the height of it. Cured had its world premiere at Outfest 2020. It is currently seeking distribution. Rating: 3/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Kino Marquee is set to release a collection of three French films that have been fan favorites at recent film festivals, yet had yet to receive mass acclaim in the United States. Some of these have appeared on Mubi, or Kanopy, but are available now to support arthouse streaming services. Here’s what I thought of them, and this format certainly works well to curate the foreign market. (Seriously, when are we getting a triple feature of Losing It, Heroes Don’t Die, and Real Love as a second part to this?!)

Burning Ghost

Burning Ghost is a transcendent small production, a fainter echo of the intimate awe inspired by Mati Diop's Atlantics last year. Judith Chemla has a haunting gaze, her pale, wanting look alone leaves her ghostly in the lens of Céline Bozon's adept camerawork. Funny enough, she isn't a ghost, but Juste (Thimotée Robart) is. She is from his past life, and recognizes him as he has come to walk the earth again. He is a collector, taking memories off of those on the streets to help them move on, and hardly knows where he recognizes the souls from. The film is beautifully shot, lighting making city streets out to be an eerie afterlife, and the intimate sequences are particularly beautiful. Reds and oranges come out at night against bright blues, burning with colors of a flame, with blue that feels hot instead of the cool or serene hues it so often is relegated to. The end result is tender, yearning, and a pleasant surprise.

Burning Ghost is now streaming online in partnership with indie theaters. A list of participating locations can be found here. Rating: 4/5 Wonders in the Suburbs

Wonders in the Suburbs is a comedy of eccentrics, but the eccentricity falls flat into dry satire and joyless quirk. A supposed satire of French municipal politics directed by actress Jeanne Balibar, and produced by actor Matthew Amalric, it's embarrassing to see this running on autopilot "comedy" from actors with the privilege to try their hand behind the camera seemingly without any passion for the craft. It feels overbaked, a slew of French stars turning up, only for it to be utter nonsense (and an absolute waste of Bulle Ogier in the furthest thing from Rivettian comedy it could be). It’s unfortunate that this comes from genuinely talented people, some of the most passionate left wing faces in French cinema, but it’s a screaming, unfunny disaster. Emmanuelle Beart is a sad letdown, at the core of some of the many cringe inducing moments. It would be nice to pride the film for its diversity, but it’s too hollow, unfunny, and pointlessly quirky for this praise. Chaotic neo-liberal utopia would be entertaining to explore, but nothing lands, and it can’t help but seem like this wasn’t just lost in translation.

Wonders in the Suburbs is now streaming online in partnership with indie theaters. A list of participating locations can be found here. Rating: 2/5 The Bare Necessity

The one issue with The Bare Necessity is that it often feels like a script perfected on paper, but never tried in reality. Other than some awkwardness, it’s heartfelt, witty, and well-defined to its own little world. Swann Arlaud and Maud Wyler shine in a story of how easily our lives can change when someone enters or leaves it. Often deadpan, it is the story of a person as a meteor, given the chance to crash into the lives of a tight-knit community, and open eyes. The film finds its feet when pride is stripped down, personality flaws ripped apart to reveal a new, humbler man, as everyone watches. When the film is clever, it's very clever, and the weak first act, and its plot contrivances, are saved by great performances, and qualified camerawork. The adapt cinematographer shows nature wonderfully, a pale, serene delight for the landscape to stretch out into.

The Bare Necessity is now streaming online in partnership with indie theaters. A list of participating locations can be found here. Rating: 3.5/5 |

Archives

April 2024

Authors

All

|

|

|

disappointment media

Dedicated to unique and diverse perspectives on cinema! |