|

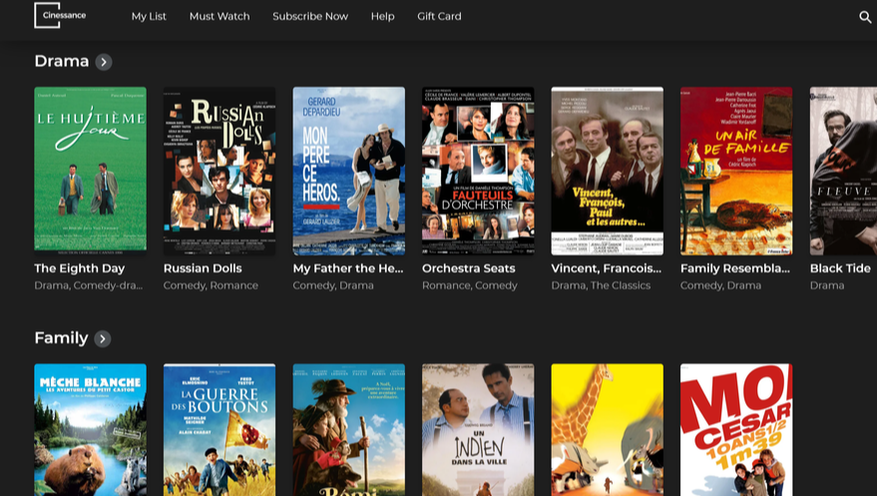

By Sarah Williams Cinessance is a new streaming service that intends to be the first US streamer exclusively for French film. As an alternative to arthouse streaming like Mubi or Criterion Channel, what Cinessance programs isn't bound as much by pedigree in critical circles or international precedent, but a subsection of French film that tends to stay within national borders. It is worth a wonder as to who tends to subscribe to specialty streaming services, whether it’s cinephiles committed to finding legal access to rarer classics, or a casual viewer who likes a particular formula. The selection favors a more traditional breed of cinema, steering clear of genre pictures, but that isn’t to say there’s no potential for the best of this populist simplicity to slip through. If you enjoyed Cédric Klapisch’s The Spanish Apartment, some deeper cuts like Russian Dolls and Family Resemblances are now streamable, and recommended. It’s also nice to see a small family section, particularly after recent online discourse as to whether non-English cinema precludes a ‘snobbish’ set of interests. The democratization of non-Anglo culture is of course commendable, especially as a selection of kid-friendly films is incredibly helpful for promoting early language learning, something harder to achieve with other, solely-adult specialty services.

Perhaps it is wrong of me to criticize a service for what is not. There is a solid start for a platform of largely '90s and '00s French film that isn’t easy to find overseas. While major arthouse features, and controversy-drivers, tend to make it across the ocean, the language of French comedy is largely lost on audiences that can access little of it. While it would be nice to see more from the era (I’m particularly partial to a lot of the '80s/'90s films by women that writer Françoise Audé championed), there is a skewed perception of popular French film in the US, and the platform does change that, by providing more of it, though near exclusively this palatable portion. In terms of the addition of more recent releases, Mélanie Laurent-starring Return of the Hero is under the coming soon subheader. It’s a lightly comedic, pleasant historical drama of small scale, and a good sample for the sort of content that Cinessance distributes. This week, the streaming platform added a hub to watch both the short and feature lineups of My French Film Festival. While the shorts are free in other places (personal highlights I’ve seen in the past from the lineup are Hold Me Tight and Little Bear), the feature film selection is more exclusive, often boasting premieres for films that do not have US distribution, this year, MFFF includes major festival titles of the past year such as Honey Cigar, All Hands On Deck, and Nadia Butterfly, as well as underseen Marguerite Duras adaptation The Lover. These films engage France, and its film culture, in a broader world context, and give a greater perspective than what the initial streaming lineup may show. This partnership shows a lot of potential for what the service can become, with events to connect a past and present of French film beyond Breathless or Amélie.

0 Comments

By Sarah Williams It's not that LGBT stories have been completely absent from film history, but they're often buried or have gone without restoration. Whether censored by their home countries and subsequently lost as so many in Germany were, or censored before production like many in the United States to become merely subtext, it's a struggle to piece together an accurate early queer cinematic landscape. In recent years as interest has risen, many of these films have slowly returned to public consciousness, letting film history fill in the gaps of what the so-called ideals of decency tried their best to hide. Now available through virtual cinemas, Kino Lorber presents three "Pioneers of Queer Cinema", three new restorations of should-be classics are packaged Carl Theodor Dreyer's Michael came in a particularly prolific era for the renowned filmmaker. Unlike later years when the auteur was creating a film for every ten years, the early part of the roaring twenties was a time of frequent releases. 1924's Michael is one thought to have been lost for years, and the new restoration is stunning. The silent gay romance isn't any less sweeping than it would be in sound, and it's eerie to see an explicitly gay film this early on but with so little reputation to its name, especially with the silent era having been filmmaking at it's most innovative technically, while only the beginning of narrative innovation. An artist falls for his model, but the young man posing falls in love with a woman, and the artist struggles to fight how he feels. While it does fall into the vein of melodrama, it's as balanced as a later Sirkian melodrama, letting its ambiguous ending gently send off the characters while still feeling real for the time. Male homosexuality was criminalized instead of ignored or looked upon as insanity due to men being seen as the sole active sexual being, and though the power dynamic is clearly unbalanced by their places in society, Dreyer is searingly honest in showing how passion fights against loneliness and later wanes, and his depiction of a gay man shut off from society never feels less than truthful. Mädchen in Uniform comes as a first for lesbian film, a first to distinctly show romance between two women. Like all firsts, it sets a precedent for tropes prevailing in lesbian cinema, specifically the outline of the boarding school film. Produced in Germany during the rise of Nazism, it's a miracle the 1931 film still exists past censorship to be spoken of today, and even besides its radical existence as a piece of representation, it maintains a fantastic film. The intimacy between the leads in the story of a young woman in boarding school struggling to adjust to discipline as she falls in love with a teacher is wonderfully performed, and the tenderness between the characters is stunningly realized in Leontine Sagan's gentle forbidden romance. Like any love between women, this romance is forbidden, and the threat of being forced to leave the school is palpable, yet never feels overly cruel. The later American remake is far more chaste, and shies away from much of the love aspect, but the 1931 original is groundbreaking, especially as the start of the tropes of the school girl romance and the age gap that have been prevalent in lesbian cinema since. Unlike the other two that fit more neatly into easy definition as LGBT cinema, Victor and Victoria blurs both sexuality and gender boundaries. The lightest of the three, and the weakest for the lack of emotional weight, this gender-bending comedy twists its characters enough times that it covers nearly all the ground for decency code-breaking. Reinhold Schünzel's 1933 story of a woman in disguise as a man, and the man she plays who must disguise himself as a woman to take her place is an outlandish one, and though being hard to believe at times, has enough heart for the cross-dressing humor to land. The two on drag as one another are cleverly disguised, and while the audience can clearly see the woman in masculine clothes, which is played for comedy, it's a wonderful early idea that gender roles are a set of performances one puts on. For years, largely in Hollywood, gay representation was largely indicated as subtext, and the common way to do so was through wearing the opposite gender's clothing as to indicate the idea of being "improper" for one's sex. Here this trope is played as the plot, and though it never gets as clearly gay as many expect of the Weimar Germany era, the play on gender tropes is more than enough of an established "queerness" for early cinema.

Kino's Pioneers of Queer Cinema collection is now streaming online in partnership with indie theaters. A list of participating locations can be found here. |

The Snake HoleRetrospectives, opinion pieces, awards commentary, personal essays, and any other type of article that isn't a traditional review or interview. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

|

|

disappointment media

Dedicated to unique and diverse perspectives on cinema! |