|

Review by Sarah Williams

A lingua franca, also known as a bridge language, is a language used for communication between people who do not share a native language. As we move through our lives, we exist in the world by how much it accepts us. It is like a language, a translation of social codes and risks we take that we translate to our own place in the world. It is hard to see the world through another’s eyes, this language of their movements, and the choices they must make, but the language that comes through art can bridge this. This is why we use cinema to see through into what someone else experiences, but this only really works when it comes from a place of authenticity. That authenticity runs through the veins of Isabel Sandoval’s Lingua Franca, a small, understated feature that feels deeply lived in.

Isabel Sandoval is Olivia, an undocumented Filipino trans woman in Brighton Beach, who works as a caregiver for aging Russian Olga (Lynn Cohen). She's working to be able to marry the man who has promised himself to her, until Olga’s grandson Alex (Eamon Farren) opens her eyes that immigration may not be the hardest factor here. There’s a tender safety between Olivia and Alex, but it’s not quite clear whose safety that is. When Alex tells her “you’re safe now”, he seems to mean himself, finally at peace where her life comforts him. Lingua Franca is a quiet lull before the storm, a calm insight into the daily rituals that come with living in a world that is set out against you. All of this is normal for Olivia, the stressors of her life are normalized here to a point where the plot isn’t her being trans and the struggle of it, and her immigration status is only relevant for the financial struggle that arises to marry her lover. These things are not the focus of her character, and Olivia is allowed to live a normal life, and isn’t defined by her setbacks, but lives them.

I look forward to a world in which Isabel Sandoval is one of her auteur generation, as the story she creates is intimate, authentic, and smartly-crafted. A one-woman filmmaking wonder in the tradition of Akerman, she directs, produces, edits, writes, and stars in this quiet slice of life, scenes from an ordinary day that feels extraordinary when we don’t live it. Having worked on this idea during her own gender transition, Sandoval acutely depicts the stresses of life with a hand that rarely wavers as one of an amateur would. While her voice may be fainter here than it could be, the film is often too slight to leave as hard of an impact as it could. There is a commendable nature to how she never goes for the cheaper emotions, no loud outbursts come here. That being said, it’s almost too gentle, no one scene stands out as memorable, and it’s hard not to wish that tenderness went much further.

Released by Ava Duvernay’s ARRAY label, this is the kind of film that benefits from this wide audience. It’s put in a place where it will be clicked impulsively, and even if that view mainly resonates as too slow for a general audience, at least this story is presented to the broadest audience it could be. So often, queer cinema is relegated to the sidelines when it comes from a place of authenticity, in favor of watered-down stories made palatable to a general audience. ARRAY focuses on this authenticity, stories against an all-white cinematic canon that prevailed for years, that will challenge this general Netflix audience if they choose to view. It is the accessibility that matters, allowing for the world to see what they may not know to seek out on their own. Lingua Franca streams on Netflix beginning August 26. Rating: 3.5/5

0 Comments

Review by Sarah Williams

A vérité-style documentary showing the formation of community through music, River City Drumbeat is a finely crafted portrait of how art can uplift us when the world won't. The story of the River City Drum Corps in Louisville, Kentucky, follows Edward "Nardie" White, and his assistant, Albert Shumake, a former member of the corps, and the music program they develop for at-risk elementary schoolers. We not only see what these kids go through in a city that tells them not to aspire to anything, but we see the two men's own struggles, and how the community they foster helps them too. It’s about the connection to and sharing of culture, and how art persists even when it is not invited in.

Using the music of its subjects for a rhythm, the constant drumming, growing more skilled as the young musicians thrive. It’s not about skill though, it’s about community, one that fosters talent and gives the young people a place to grow at something. The persistent drumbeat helps the pacing quite a bit, where the film slows there’s the music that keeps it from dragging too much.

The lack of talking head interviews keep the film from feeling blandly educational. Blending the stories of this community, including the escape from the cycle that is poverty, some mentions of family death (the murder of White’s granddaughter and his wife’s cancer) that may be upsetting for some viewers, and a discussion of racism, language, and bias from the education system itself, smoothly into the rest of the footage to make this a story of triumph, not suffering. It is able to tackle these struggles, many of which are systematic, in a way that shows that joy can be found, that people can work together, and make it past this, by showing the light instead of dwelling upon these tougher parts of life.

Overall, River City Drumbeat’s final product is a heartfelt, uplifting story about the power of community over prejudice. What it lacks in originality of craft, it makes up for in heart. It’s a powerful, compact story of triumph, and a love of the arts, and a testament to teamwork that makes it a great film to show mature kids. While showing one school in the south, it provides a leading example for what can be done to uplift young people by giving them an outlet for their energy, something to look forward to, and someone who believes in them having something to aspire to. River City Drumbeat is now streaming in partnership with indie theaters. A list of participating locations can be found here. Rating: 3.5/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Ever want to see some of the most insufferable, empty people you will ever meet on a screen brutally killed by crocodiles? Well you’re in luck with Black Water: Abyss, as everyone is so unlikeable you’re not only rooting for the beast, but wanting to be it.

A sequel to the 2007 Australian sleeper hit, Abyss loses steam in any semblance of narrative or investment by refusing to develop its characters beyond pests to be exterminated. Eric (Luke Mitchell) and Yolanda (Amali Golden) lead the way, with Jennifer (Jessica McNamee) and Viktor (Benjamin Hoetjes) in tow, on an impromptu adventure into a subterranean cave Eric is intrigued by. The trip soon becomes the romantic getaway from hell as the four are trapped in the increasingly narrow cave tunnels by a storm, and a hungry reptile is ready to snack. Admittedly, the cast of characters does play the game down there well, and no one makes dumb decisions, clear they know what they’re getting into. They aren’t whiny, don’t squabble unnecessarily, but everyone is so devoid of personality it's hard to care past the spectacle of the kill itself. They seem like bots at times, pre-programmed straw-men who make most of the right decisions, except for what kills them. These kills are well done, sparing much of the blood and gore for what we don’t see, a creature that rarely shows its face spare for a creeping sense of dread, the best case scenario for horror beyond the big-budget name brand flicks.

At times feeling like a reptilian knockoff of The Descent, it does get some solid scares in. If you’re unlike me and are able to be unsettled by a horror movie that doesn’t give you a tolerable audience surrogate, or at least someone to pity and be invested in, it’s a fun, if shallow ride at times. Whereas The Descent knows itself as high energy, shock driven, and gutsy, Black Water tries to ride on its scaly menace that does not quite provide the fear factor without an existing fear factor outside a few gimmicky jump scares. The scariest thing here is nature, and the tropical storm keeping the pair of couples down, rather than any beast that may come.

Black Water: Abyss almost works better as a disaster flick than anything else, but its lower budget and unmemorable performances keep it from going down with the greats in that genre. It’s mindless popcorn entertainment with a nice setting, the kind of late night ‘scary movie’ that starts to blend together with little difference outside the placement of jump scares. It’s not poorly made for a sequel this late in the game from the original, which does not share any characters, but it begins to blur together with the many similar films on the market, it's hard to find any stand-out element, or hook, for anything beyond the die-hard genre fan. Black Water: Abyss is now available on VOD. Rating: 2/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Playfully intimate, Simon Amstell's Benjamin is a love letter to falling in love with the concept of being loved. A slight indie rom-com that's genuinely charming, it's the film we've been asking for to make the genre gay. Light, gentle, and still surprising Ben Whishaw doesn’t have a role anywhere in it, it’s a hidden gem of easy viewing with a massive amount of heart, not to mention the Mark Kermode cameo.

Merlin's Colin Morgan plays a film director, the titular Benjamin, on the verge of premiering his second film. He is introduced to a young French musician while at London Film Festival, and is enamored at first watching from a distance. The two soon hit it off, and it’s a slight love story filled with that messy awkwardness from the beginning of getting to know someone beyond just watching them. Noah (Phénix Brossard) has this natural, teasing chemistry with Ben, who can say anything, joking about French stereotypes constantly, and is enamored just the way Ben is when he sees Noah sing that first night. Almost Xavier Dolan-esque in its brightly colored gay love story about two pale skinny guys with dark floppy hair (the only kind of Dolan love interest) meeting and falling head over heels, it avoids much of the enfant terrible’s melodramatic tendencies. Where the young auteur goes for heartbreak and over the top drama, Amstell’s film goes for tender laughs in a way that may appeal to those who’ve tried to like Dolan, but just can’t get behind the height of his maximalism. Nobody is perfect in this sweet little rom-com world, and though the romance is idealized, it is put on the same pedestal as the typical heterosexual rom-com (and even those seem to be disappearing), and never does it make the characters seem any different.

Neither man is given a struggle of toxic masculinity, allowing a refreshing save of tenderness to wash over the film. A scene where Noah softly washes Ben’s hair in the bathtub comes to mind, eyes shut as they touch, and it's so rare to see two men allowed their desire without any hardness. There's a warm, grainy haze washed over the whole film, like we are peering into an archive of memories of woozy nights spent falling into love, projected on a screen later on in the relationship. They’re the kind of memories you’d show the world, the moments in your love that create a neatly packaged retail book that make it all look so easy.

As a friend of Ben once says, “You only like people who are well lit and weak”. There’s a love letter here, drawn often from Amstell’s own experiences, to loving the easy targets, those that you are sure will love you back from a pretty picture. While this isn’t always the soundest way to go about things, as sometimes love is tough, it’s refreshing to see the two men slip together so easily. Benjamin may not be the meatiest romance, but it has a massive heart, and is the kind of simple gay romance the internet has been begging for. Benjamin is now available on VOD. Rating: 3.5/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Perhaps the biggest sell of The Wolf House is its radically unhinged animation. It jumps between 2D, 3D, stop-motion, and anything in between as it scraps to follow its story. Rather than feeling messy and tacked together, the end result is a memory book of fairytale horror and reality. It works because the 2D interacts with the 3D, styles melding on screen at the same time to an effect of collaboration of multiple artists coming together to tell a story like it's being retold around a campfire by a group that knows it well.

There is no respite from the horror of this nation, this trapped place in which there has never been a way to flee, and it's a cold reflection of reality. It is the story of a young girl, from Chile's Colonia Dignidad, a German madman, a child predator fanatical with misplaced religious devotion. He has turned this land into a military dictatorship in service of Augusto Pinochet, and she is in danger after coming into trouble for losing three pigs. This last part sounds like the setup to a children's story, some fairytale book read before bedtime. And maybe it does seem to be so from here, as we have three pigs, and we have a house — the wolf house in the woods that our young heroine shelters in, but the broken fairytales of reality are far darker than anything in fiction.

The text grows richer knowing the history of Chile and the events that may parallel the story, but much of that imbued history lesson can be learned from watching it all play out. Would the film play better with the context? Yes, but the learning experience, even though shallower, still plays well for an audience not raised with this knowledge. It's colonial trauma projected onto the life of one young girl, and her youth is only clearer when her story is told through a classic children's tale, and we see the contrast between the typical sheltered childhood, and the fear in her life. The stop motion models are painted, cracking and messy, like a child's experiment come to life. The cobbled together style is eerie, with animation so focused on perfection it's unsettling to see the cracks in these models.

It's not the only recent animated film to tackle raw societal struggles through stop-motion in a powerful manner. Emma De Swaef's This Magnificent Cake! is a soft felt recreation of the horrors of Belgium's imperialist acts. It covers the pain of colonialism in this soft fabric so it's more easily digestible before the subject matter is broken down, while The Wolf House bares the messy underbelly of power struggle early on. This melding of animation is often dark and clashing, the power dynamic clear even within the medium. An exploration of trauma through the myths of childhood, perhaps The Wolf House makes the much needed statement that America has fallen behind on that animation is a medium, not a genre, and the surreality of the tools used to make a film do not have to make it any less raw. The Wolf House is now streaming in partnership with indie theaters. A list of participating locations can be found here. Rating: 4/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Time comes with many conditions, but it also bears a potential for change. Sometimes this change comes with progressive attitudes, no longer feeling the need to destroy anything that challenges our worldview, but sometimes this change is forced, a trial to push away some unwanted concept. In the case of Kristine Stolakis's feature documentary, Pray Away, time, for many, is hope that they can change themselves to make the world easier.

So-called reparative therapy has originated in its prominent form within evangelical church groups. It is an attempt to cure one of homosexuality, whether by force of another, or voluntarily. It makes the subject overanalyze their attraction, and blame the world around them for leading them down some sort of "sinful path". This idea only works if it is viewed as a subconscious choice for the participant, and the "ex-gay" graduates of the programs often say they have chosen a new life of normalcy. This is true somewhat, but it isn't that they have made the choice of sexuality, but that of repression. It’s fairly dense subject matter that’s received quite a few depictions, but few outside the realm of fiction fully dig into why this happens, and what the exact psychological effects are. This one is a little different than others, as we see the supposedly cured “ex-gays” who lead these programs, trying to help others become like them, even if they themselves are still actively repressing their own desires. We hear from the former face of a group called Exodus, Josh Paullk, who admits that even he never changed, and that he lied that he didn’t still have feelings for men. Since leaving the organization, that he says he truly believed had the power of change, he moved to Portland with his male partner.

The subject is handled showing voluntary conversion therapy as what it is: a form of self harm. Whether it comes from societal pressure, religious conviction, or any other fear of one’s same-sex attraction, this process of lying to oneself and the world, and treating a part of the self as a form of evil is incredibly damaging. For some, they panic, and for others, they turn further inwards. Trained self-hatred leaves scars, and these Christian fundamentalist programs are exactly that.

The hardest to watch of the four threads in the documentary is that of Julie Rodgers, who was held up as the teen ex-lesbian face of the movement after being forced into a reparative program at sixteen. Some parts, like enforced adherence to gender roles (girls must wear makeup, sports are too masculine), come off as almost cartoonish for these programs. Then the reality sinks in: these are young teenagers being trained to hate themselves. She says she’ll always remember being a teenager who was told she was a bad kid for having acknowledged part of who she was, and this is where we see just how much these teachings stick — even when those who’ve gone through them have left and denounced them. When we cut to Julie in the present day after meeting her through archival footage, we get to watch her prepare for her marriage to a woman, and we see the happiness that comes with freedom, as well as how the effect never quite leaves. This afterimage is what sets Pray Away apart. Instead of beating down the misery, it shows that there has always been a future possible for the subjects who had tried to fix something they were told was wrong with them. We see them happily married, or living as themselves, years after what they had been through, and we can see that future instead of lingering on wondering if maybe it could have worked. When we are only shown the misery of conversion, we are led to believe that it is an ending, when it is very much so. Pray Away depicts it as a painful false path, but that there’s always a way back, and that’s when it hits hardest. Rating: 4/5

Review by Sarah Williams

Before touching upon the rich text of Kantemir Balagov's debut feature Closeness, let's take a moment to touch upon the spectacular knitwear in this movie. There is truly unparalleled sweater quality here. The rest of the film is much less warm and fuzzy, following a Jewish family in the '80s, when their youngest son and his wife disappear. They are held for ransom, an amount high enough to close their business and force them to seek help from the surrounding community in hopes of return.

Stemming from a funding initiative by legendary Russian filmmaker Aleksandr Sukurov, it's an astonishing beginning for such a young filmmaker. It's the start of the weighty themes of fraught family and human connection in last year's Beanpole, only here the story is set within the confines of a strict Jewish community. Closeness has that same intimacy, veering tightly into the lives of its characters to watch their bonds break apart under stress. Strong performances flood the screen, particularly commendable is Darya Zhovner, who takes her heroine, Ila, and her refusal to marry to pay ransom to a higher level. Ila is denied a voice repeatedly, yet she persists, perhaps to see an end to her world surrounded by senseless violence and power struggle. Iya's tomboyish nature and her realistic consideration of debts owed to family make her an incredibly compelling protagonist, an entry point to an otherwise overbearing world. The film is shot with a warmth despite the coldness of the cruel world depicted, an emotional hotness as the camera lingers upon bodies wrapped in a desperate embrace, or upon the fabric of the characters' clothing as we're given respite from emotionally fraught faces. Color is key, especially in the final moments, though exactly how so would spoil the surprise.

The film has become somewhat notorious for a sequence utilizing real footage of Chechen rebels killing a soldier. This scene is essentially a setup for anti-Semitism of this society to be shown, but it feels irresponsible not to simulate such a small moment. Perhaps the footage is used to create conversation around the film's premiere, but it's distribution overseas has only come a couple years later after the success of Kantemir Balagov's follow-up Beanpole with international audiences. It's a major ethical lapse that detracts from an otherwise strong feature, a head-scratching moment as to why we would need to see a real life ended on-screen, even if the footage had other origins. Kantemir Balagov defends the use of a real hate-killing from an archive, claiming a simulation would not have the same emotional impact (though this impact has resulted in much backlash).

In Russian, the title does not translate directly. It is not a direct "closeness" that this word refers to, but a squeezing, cramped situation, a confinement of sorts. What the film does best is an emotional confinement, never letting the audience leave the headspace. It's a typical arthouse drama that takes the side of emotion over minimalism, something that would later be taken farther with Beanpole. Much of the latter's lingering intimacy, a love broken by the stress of a cold world, and the warmth found in capturing the light that reflects off of these acts is present here in prototype, though more unsure, but certainly no less accomplished. Closeness is now streaming in partnership with indie theaters. Rating: 4/5

Review by Sarah Williams

The Dilemma of Desire is an entire movie dedicated to the clitoris. Focusing on the underexposed female organ, it's a story of reclaiming sexuality. Not only do we learn an anatomy lesson, but there's the sociology around it, and an unveiling of why so little is common knowledge. It's an exposé on the suppression of women's sexual health, and it's unsettling to see how commonplace it is. As a long-form news story of sorts, Maria Finitzo's film is a cultural acceptance and reclamation of the clitoris in the purest form. This education is referred to as "cliteracy", a portmanteau for understanding women's bodies. It's a word that seems crude at first, but is no more so than any of the male versions that are commonplace.

It's a shame that for so many important topics, the film feels shallow and unrefined. It shifts between a sex education lecture, a showing of yonic art, and then pivots to how much it's taught in schools. The topics discussed aren't all things that would be learned at the same age, leaving a majority of the film much less useful based on the viewer's age. There is also a largely one issue view taken, meaning the film lacks any discussion on how these facts and access to resources may change based on a woman's sexual orientation, ability, class, or race. This intersectionality makes it harder for any nuance to come with the content.

While the film is jumping around, it does highlight some chilling facts about how little we are taught about our own bodies. “In the USA, only 24 states require some sort of sex education, only 13 require that the information be medically accurate.” Less than half of the country requires anything, and only a quarter mandates that that must be real science taught. It's a scary fact, this misinformation, and it does need to be highlighted. What is taught is largely geared towards and about young boys, leaving the rest in the dark over how anything actually works.

The main issue is the film doesn't quite know its audience. The overt feminist themes that are in the premise, title, and marketing, so the audience is already going to be on its side. Yet the film chooses to start from the beginning, blending the biology and sociology lesson on the clitoris with a primer on feminism these viewers simply don't need. The key parts would be best taken out as a short documentary, more of a grab-and-go format to dispatch and garner awareness of how little we know. The content of the film is all what needs to be marketed to young women, just not as a whole. Some parts of the film are key to when hitting puberty and discovering the body, while others are for when first becoming sexually active, and these are very different contexts. As an educational work outside of learning these things for the first time, The Dilemma of Desire is a well-presented look at what information is withheld and what the truth is, but it struggles to understand what it wants its audience to be, and how to speak to them. The Dilemma of Desire was set to debut at the cancelled 2020 SXSW Film Festival. It is currently seeking distribution. Rating: 3/5

Review by Sarah Williams

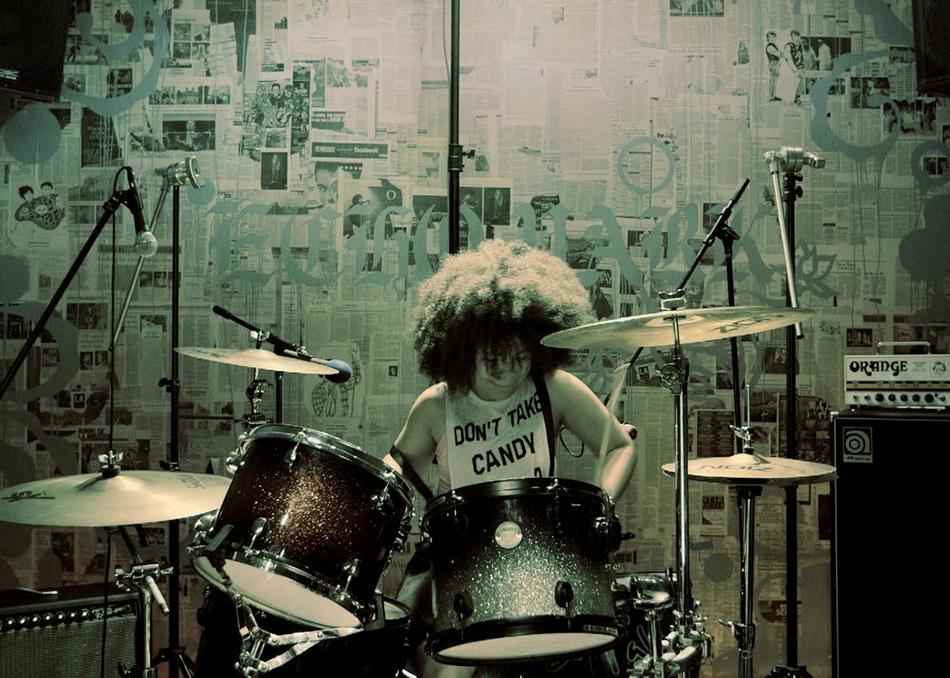

Tomboy (no, not the Céline Sciamma film) is a grab-bag of tales of women drummers making their way through a man’s world. Many will be drawn in for the archival footage of Courtney Love and Hole at practice through the eyes of drummer Samantha Maloney, but the other stories are just as compelling. The true breakout is teenager Bo-Pah Sledge, whose pop group formed with her three sisters reveals a charismatic young musician under the radar.

Female masculinity is oft-avoided as a touchy subject, but the film touches upon it well. Aside from the instrument, what these women have in common is a defiance for gender barriers that hold them back. This comes in varying levels, with some women pushing back against femininity in all cases, in the case of Chase Noelle and her band Boytoy, while others are only concerned with the limitations their gender seems to put upon them on getting to play music, and are content with the social roles. One woman talks about using empty toilet paper rolls to pee standing up as a kid, while a young girl has shelves of My Little Pony toys — proof that these women’s experiences and presentations are as varied as the music they made. Industry veteran Bobbye Hall, who has backed up Bob Dylan, as well as many big names in Motown, is less outspoken compared to her younger counterparts, refusing to go in depth as to how hard it had been for her as a black female drummer. This doesn’t make her less of a feminist, just more hardened and weary of the industry. Neon-glazed concert footage mixed with grainy home video gives the film its punk rock aesthetic. Others have criticized amateur camerawork, but the DIY nature puts it further into the throes of the music world. The sound is layered between clips so that it flows wonderfully, avoiding stretches of silence by blending music, voices, and the dull roar of a basement crowd. The beating of sticks on symbols and drumheads is a constant, and it is this sound that moves the film along. The opening narration talks about how the drummer is the one who always must stay on beat, because they are what holds a song together and can cover mistakes of others, and that is the same for the documentary as well as a song. Director Lindsay Lindenbaum assembles a warm portrait of the women’s lives around the music without going biographical. We hear a hint of "Jingle Bell Rock" on a holiday, or see vinyl records of the music they grew up with, and we feel like we know these women a little better.

Generational growth and connection shows these drummers shared experience, how the ways women move through the music world has changed, and how some parts remain deeply rooted. We see older subjects talk about being the only girl in the music scene when they started, while we meet another young subject who talks about a relationship with a bandmate. There is a startlingly good handle on sexuality and gender, portraying the effects of these on the battle to be heard with nuance, as well as touching upon how race changes the entrance to the music world. It isn’t a perfect intersectional discussion, but a variety of voices (notably by having half the subjects being black women) are brought to the table to show the many experiences. Noelle’s story is handled a little more roughly than the others; she’s the most outspoken in her feminism, and often preaches to the camera, making generalizations that not all the women share. Hall refutes a slightly egoist decry from the younger woman that the drummer has the greatest importance by talking about listening to the other instruments to create the ideal sound.

The feminist leanings are firmer at the start, slowly letting up from direct statements to the point the film is then solely about the music. We hear more of the music women love to create, and can fill the original “women’s fight to be heard” narrative in ourselves. The focus is lost a bit halfway through, and a central thesis is never developed, but it’s a solid, well-rounded view of the music industry that’s incredibly engaging, and a rousing success overall. Tomboy was set to debut at the cancelled 2020 SXSW Film Festival. It is currently seeking distribution. Rating: 4/5

Review by Sarah Williams

We Don’t Deserve Dogs is a film whose subject matter lives up to its title. All about the good that comes with our canine furry friends, different scales of four-legged kindness are shown. With production travelling eleven countries in just thirteen months, the documentary is an impressive bit of filmmaking with just a two person team (who also happen to be a married couple), director and cinematographer Matthew Salleh, and Rose Tucker as both producer and editor.

2020 seems to be the year of nonfiction and quasi-documentaries about dogs. The festival slate has had plenty about sick and injured dogs this year, so it's a breath of fresh air to see them featured in something more positive. This episode in the domestic dog saga is so filled with love and reverence it’ll surely find an audience, the kind of late night comfort food you put on after a bad day at work. A world tour of dog stories, We Don’t Deserve Dogs has many stamps on its passport. We see how pet dogs help child soldiers in Uganda, the passersby of a pub in Scotland, and hear the story of a dog walker on the streets of Istanbul. There’s working dogs too, some that hunt for truffle mushrooms, some that stand watch, and some that are just there to guide. There’s some love that transcends culture, and that same love transcends species in the ways of the dog.

Not all of the stories are as cleanly shown, and everyone will probably have a least favorite segment, but it jumps around so much you’ll always have something better coming up. Of course, these jumps across the globe do feel a bit disjointed, but it’s usually in more of a montage style than messily stitched together. There’s often not much connecting these vignettes other than the shared love of dogs and what they bring us, so it’s not a film for those who aren’t already animal lovers.

The worldwide array of people and their dogs, and the diverse array of meaningful connections and mutually beneficial relationships is a beautiful thing. The score is gentle yet paces the film along, and it’s shot nicely for a smaller documentary, with some great static shots of the countries visited. The camera often gets down on the eye level of the dogs, and they come close to the camera to look it in the eye. It’s hard not to want to be there with them! We really don’t deserve dogs and what they can do for us. A dog can’t understand everything we say and do, yet they somehow find a way to help anyway. There’s a lot of heart on screen, whether it be from behind the camera, or from the dogs and the people they bring joy to. It’s a lovely interspersing of “hero dog” stories and the mundane roles they take, which prevents it from ever becoming too heavy. We Don’t Deserve Dogs is the feel-good film of a festival that never was. We Don't Deserve Dogs was set to debut at the cancelled 2020 SXSW Film Festival. It is currently seeking distribution. Rating: 3.5/5 |

Archives

April 2024

Authors

All

|

|

|

disappointment media

Dedicated to unique and diverse perspectives on cinema! |